Inherited IRA withdrawal strategies: Maximizing tax savings

October 16, 2023

By Rob Greenman, CFP®, and Alex Canellopoulos, CFA, Vista Capital Partners

In the realm of tax planning and wealth management, one constant persists: change. As professionals in this ever-evolving landscape, we understand that adapting to new regulations, tax laws, and market conditions is an integral part of our role.

Recently, one meaningful change that has impacted wealth planning strategies is the introduction of the 10-year distribution requirement for inherited IRAs of non-spouse beneficiaries. This alteration brings forth a fresh set of challenges and opportunities for inherited IRA beneficiaries. However, with the guidance of skilled wealth management professionals and CPAs, optimal strategies can be identified and executed.

Non-spouse beneficiaries fall into one of two camps: those in which the original account owners died prior to taking RMD’s themselves – and those in which the original account owners already started taking RMD’s.

The rules are relatively straight forward for non-spouse beneficiaries where the account owners died prior to taking RMD’s. The beneficiary has no required withdrawals in the first nine years – but the entire balance of the account must be withdrawn within 10 years of the original account owner’s death.

For those where the original account owner died after RMD’s already started, the beneficiary is required to keep RMD’s on pace per the original account owner’s RMD schedule. The required withdrawal percentage ratchets up each year – a would-be-75-year-old withdrawal rate is 4.4%, 80-year-old at 5.4%, and 85-year-old at 6.7%. Any remaining balance of the account must be emptied within 10 years of the original account owner’s death.

All non-spouse beneficiaries are left with some planning opportunities given these new rules. Without the guidance from trusted advisors, it is likely that they will forgo the opportunity to explore the most tax-savvy route. In this article, we will outline two baseline approaches: waiting until year 10 for a lump-sum distribution versus spreading the distributions evenly over 10 years. We will also highlight situations in which advisors should consider customizing the withdrawal strategy based on the unique circumstances of the individual. Finally, we will discuss financial planning levers that advisors can employ to complement or enhance the effectiveness of the inherited IRA withdrawal approach.

Baseline Assumption: When in doubt, spread it out

Defer, defer, defer. This is typically a sound tax management strategy. In the context of inherited IRAs, this approach would lead beneficiaries to wait until the end of the 10-year window to distribute the account. By doing so, they can defer taxes on both earnings and withdrawals. However, this seemingly straightforward approach may not always yield the best results, as it could trigger an increased marginal and effective tax rate in the 10th year.

An alternative strategy is to spread distributions evenly over the 10-year window. While this approach generates a known tax cost in years 1-9 that might otherwise be avoidable, it can be advantageous, particularly when the effective tax rate on distributions is relatively low. This strategy ensures a more consistent and potentially tax-efficient distribution pattern.

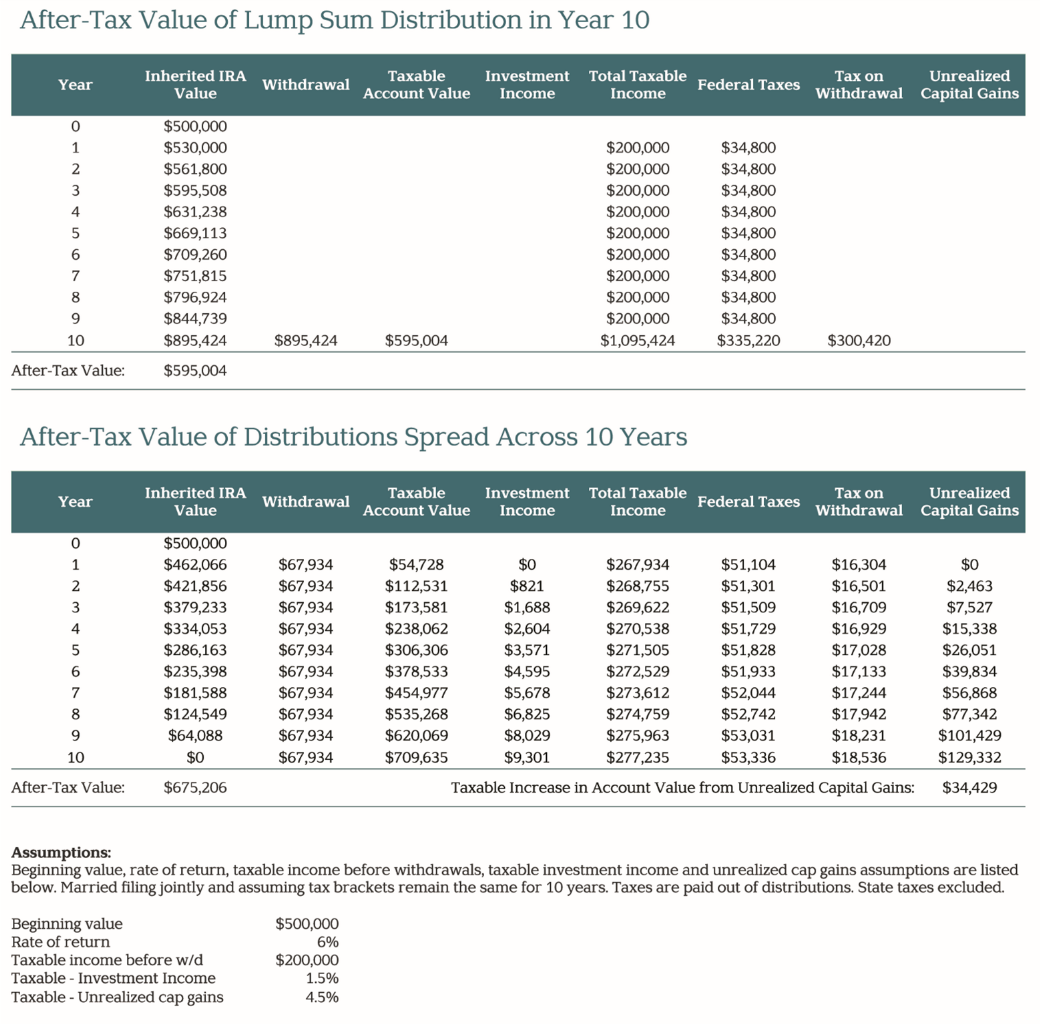

To illustrate the potential difference in federal income taxes under the two approaches—lump sum versus spread—we can consider some baseline assumptions and run some numbers. As seen in the examples outlined below, there can be substantial tax savings associated with the "spread" strategy.

In this paper, we present two comprehensive approaches for inherited IRA investors, each of which is interpreted through two distinct data tables. In both scenarios, we begin with an initial inherited IRA balance of $500,000, with investment returns consistently set at 6%. Additionally, in both cases, investors report $200,000 in taxable income annually, separate from any taxable income stemming from the inherited IRA account. The first table illustrates a strategy wherein the investor allows the inherited IRA to accumulate without withdrawals until the culmination of year 10. Although this approach maintains low taxable income levels from years 1 through 9, it results in a substantial $895,000 inherited IRA distribution in year 10, incurring a $300,000 tax liability. The investor started in year 1 with a marginal tax rate of 24% (effective tax rate of 17.4%) and jumped to the 37% bracket in year 10 (effective rate of 30.6%). Consequently, the net amount retained by the investor after disbursing the inherited IRA and paying taxes stands at $595,000.

Moving forward, the second table highlights an alternative approach where withdrawals are evenly spread over the 10-year timeframe. Withdrawn amounts are adjusted for tax considerations and subsequently invested in a taxable brokerage account, taking into account modest dividends, interest, and realized gains. The cumulative taxable income in years 1-9 is notably higher than that of the first investor described in the initial table. Nevertheless, by distributing tax payments over a decade, the investor circumvents a substantial single withdrawal, staying within a relatively low tax bracket throughout the 10-year period. The investor consistently hovers in the 24% marginal tax bracket (19.2% effective). The final value after accounting for all taxes reaches $675,000. This discrepancy of $80,000 in ending values underscores the considerable impact that choosing the right approach can have on inherited IRA withdrawal strategies. Running the numbers for each investor’s unique situation can provide invaluable insights to help navigate the optimal inherited IRA withdrawal approach.

Baseline Assumption: When to kick the can until year 10

So, if spreading it out should be the default strategy, when does it make sense to kick the tax can down the road? Simply run the numbers on leaving an inherited IRA balance alone, compounded at a reasonable rate of return over 10 years, and evaluate the new effective tax bracket. If there is not a meaningful jump in the tax bracket by distributing the entire inherited IRA at the end of year 10, then this could be a reasonable approach.

Baseline Adjustment: Substantial income changes

Example 1: High-Earning executive

Imagine a high-earning executive who is five years away from retirement. In this scenario, waiting until after their W-2 income falls off the tax return could result in a much lower effective tax rate on inherited IRA withdrawals. By strategically minimizing withdrawals during their high-income years, they can reduce the overall tax burden.

Example 2: Capital gains spike

Another situation to consider is when a couple sells a house, and their taxable gains significantly exceed the $500,000 tax-free gain exclusion. In such a year, it makes sense to minimize additional tax liability by limiting inherited IRA withdrawals. Similarly, periods of robust stock market performance leading to a rebalancing event with higher-than-normal realized gains in a portfolio are ideal times to exercise caution with inherited IRA distributions.

Baseline Adjustment: Considering A Home Move

Example 1: State Tax Considerations

Relocating from one state to another can have a profound impact on the appropriate inherited IRA Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) strategy. For instance, moving from Washington to Oregon presents a significant tax difference. In Oregon, inherited IRA withdrawals are subject to a 9% tax. Therefore, it would be optimal to accelerate withdrawals while still a resident of Washington to avoid this tax liability.

Example 2: Local Taxes

Moving to a new city or county can also affect the tax landscape. Some areas, like the city of Portland, impose additional taxes for services such as pre-school and homeless support, which can reach up to 6%. For individuals considering a move to evade these local taxes, it makes sense to limit inherited IRA withdrawals while still subject to higher tax rates, ensuring greater tax savings.

Baseline Adjustment: Social Security & Medicare considerations

Example 1: Social Security timing

For individuals who anticipate receiving social security income within the 10-year inherited IRA distribution window, careful planning is essential. Let us consider a 62-year-old beneficiary who inherits an IRA and plans to defer filing for social security benefits until 70. To optimize their tax strategy, it may be advisable to spread inherited IRA distributions evenly over the first 8 years. Under this strategy they would drain their inherited IRA right before social security income kicks into gear. This could smooth their taxable income and potentially mitigate any tax bracket creep that might occur by loading up inherited IRA withdrawals and social security income the same tax year(s).

Example 2: Managing Medicare's IRMAA

Medicare's "income related monthly adjustment amount" (IRMAA) is structured around a cliff system, where exceeding a bracket threshold can result in higher monthly payments. If an individual has already crested an IRMAA bracket threshold, it might make sense to accelerate inherited IRA withdrawals up toward the next IRMAA bracket (but carefully not going over the next cliff!). By doing so, they may fall into a lower IRMAA bracket in future years, potentially reducing their Medicare-related expenses.

Financial planning levers to consider during the 10-Year window

In addition to these specific strategies, there are several levers that advisors can employ to manage taxable income during the 10-year inherited IRA distribution window. These can be utilized to enhance the effectiveness of the inherited IRA withdrawal strategy selected by advisors.

1. Maximize retirement plan contributions: Ensure that employee deferrals to retirement plans are maximized to reduce current taxable income. This can include contributions to 401(k)s, 403(b)s, or similar employer-sponsored plans.

2. Non-Qualified deferred compensation: Plans Individuals with the ability to defer W-2 earned income through participation in non-qualified deferred compensation plans should consider enrolling. The amount of compensation eligible for deferral and distribution of funds vary by employer. At Nike, for example, eligible employees can defer up to 100% of three different sources of compensation: next-year’s base salary, performance sharing bonus, and long-term incentive plan compensation.

3. Health Savings Accounts (HSAs): Maximizing contributions to Health Savings Accounts can provide a double benefit: tax deductions when contributing and tax-free withdrawals when used for qualified medical expenses.

4. Stock compensation plans: For those with stock compensation plans that offer a choice between stock options and restricted stock units, selecting stock options may offer greater flexibility in timing income recognition events. Restricted stock units typically trigger income recognition at the time of vesting, while stock options allow more control over when to exercise and recognize income.

Conclusion

Navigating the intricacies of inherited IRA withdrawal strategies can be complex, but the potential for significant tax savings makes it a worthwhile endeavor. As wealth management professionals and CPAs, our role is to collaborate, educate, and guide clients through these decisions, adapting strategies to their unique circumstances. In the ever-changing landscape of financial planning, our ability to adapt and find optimal strategies given the hand we are dealt remains a testament to the value we bring to our clients.

About the authors

Rob Greenman, CFP®, is Chief Growth Officer and Partner at Vista Capital Partners. Alex Canellopoulos, CFA, is Head of Research at Vista Capital Partners.

Vista Capital Partners is a wealth management firm in Portland, Oregon, serving clients with $3 million or more to invest. Learn more at www.vistacp.com